WHEN LIFE HANDS YOU LEMONS, MAKE CINCO DE MAYO

In one California town, a holiday co-opted by beer companies has roots in a celebrated citrus crop

What’s with Cinco de Mayo, anyways?

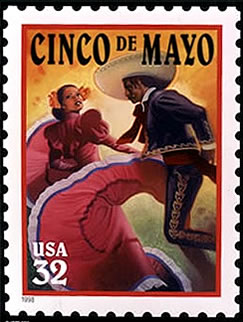

Corporate advertisers treat it as the de facto Mexican Day, if not Latino Day, in this country. In 1998, the United States Post Office issued a Cinco de Mayo stamp featuring two folklórico dancers. In 2005, Congress passed a resolution making Cinco de Mayo an official national holiday to celebrate Mexican-American heritage. And it’s customary for presidents to celebrate Cinco de Mayo on the White House lawn with margaritas flowing, mariachi music playing, and dancers in brightly colored traditional costumes.

Don’t they all know that Mexican Independence Day is actually September 16?

Growing up in rural Zacatecas, Mexico, in the early 1970s, holidays and festivities were big community-building affairs. I attended fiestas with tamborazo-style band music, rodeos with charros showing off their roping and riding skills, and the religious procession honoring the town’s patron saint. What I remember most, though, was El Grito, the traditional cry of “Viva Mexico!” to commemorate Mexico’s independence from Spain on September 16. Like Christmas, the holiday is celebrated on the eve of the big day, and the day itself. But I have no memory of Cinco de Mayo, at least not before migrating to the United States.

It was in my elementary school’s bilingual education classroom in Ventura, California, that I first learned about the holiday, which had been incorporated into lesson plans and school assemblies on cultural diversity. In high schools at the time, Mexican-American students began organizing their own Cinco de Mayo celebrations to show off their...