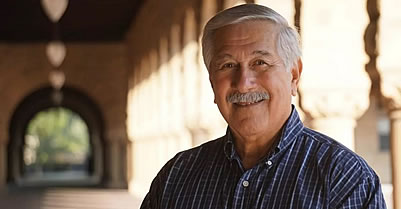

ANTONIO RIOS-BUSTAMANTE, PIONEER OF CHICANO STUDIES AT UCLA, DIES AT 75

LOS ANGELES - Antonio Ríos-Bustamante held several titles throughout his life – dad, historian, activist and husband. At UCLA, he was known as a “walking dictionary.” .

Ríos-Bustamante, a pioneer of the field of Chicana/o studies, died April 19 at 75 years old. A Santa Monica local, he received his doctorate in United States history from UCLA in 1984. A historian of the early American west, he taught at UCLA; UC Santa Barbara; California State University, Long Beach; the University of Arizona and the University of Wyoming, among others, according to William Estrada, the curator and chair of history at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Estrada said he first met Ríos-Bustamante around 1975 when the latter was a teaching assistant under Juan Gómez-Quiñones, who co-founded UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center. While most graduate students wore Levi’s, Ríos-Bustamante stood out by wearing suits, always having pens available to use, his intensity, and his vast knowledge of history, he added.

“Antonio was the kind of person that shared information,” he said. “He shared knowledge with anyone who was interested in learning. I don’t always run into people like that in my academic career.”

Ríos-Bustamante, a 10th-generation Angeleno, was a descendant of California Native Americans and early Mexican settlers in Southern California, Estrada said. During his early work at UCLA, Ríos-Bustamante was a scholar-activist, working alongside other notable historians of Latin America such as Gómez-Quiñones, Antonia Castañeda and Rodolfo “Rudy” Acuña, Estrada added.

Ríos-Bustamante was a community organizer in the Bay Area before he studied at UCLA and became a skilled mapmaker, said Luis Arroyo, a professor emeritus of Chicano and Latino studies at CSU Long Beach.

Devra Weber, a professor emeritus of history at UC Riverside who also studied with Ríos-Bustamante at UCLA, said she remembered him as always having a briefcase full to the brim of documents and readings. Still, she added, he always knew exactly where things were.

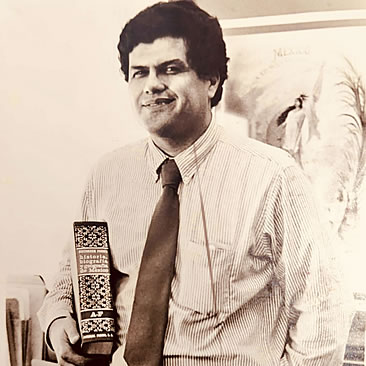

Ríos-Bustamante was part of an early generation of historians who tried to grow and legitimize the field of Chicano studies, Weber said. In 1981, with the City of LA’s bicentennial approaching, Ríos-Bustamante and Estrada collaborated on a public history exhibition called “Images of Mexican Los Angeles, 1781-1981,” which first opened at East LA College and focused on how the Mexican community flourished in the city, Estrada said. The two continued their collaboration with a project for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, titled “The Latino Olympians: Latin American Participation in the Olympic Games, 1896-1984,” a 10,000-square-foot exhibition that took place at the Pico House, he added. Estrada said Ríos-Bustamante began a movement to build a museum in LA dedicated to Latino history after the success of their initial exhibitions and exhausted whatever money he had for the efforts.

Estrada added that he believes the eventual founding of La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, a museum and community hub dedicated to Latino culture, can be traced in part to Ríos-Bustamante’s work. “There is a very serious effort going on to build a National Museum of the American Latino,” he said. “That movement can be traced directly to Antonio’s efforts.”

Eva Rios-Alvarado, Rios-Bustamante’s daughter, said she remembered her dad as an “imaginative and responsible” person. Anytime she asked him a question, he would respond with a lecture’s worth of information, she added.

Rios-Alvarado said when she was around 13, her father took her to a conference hosted by the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies. Her father’s passion for Latin American history and the conference as a whole left a lasting impression on her, adding that while there, she learned about the daughter of one of her father’s colleagues taking part in a hunger strike for justice.

“I wasn’t able to put that together until I was older, but that really impacted my formation of the world,” she said. Ríos-Bustamante’s impact was wide-reaching, as he started the first bilingual radio station in Wyoming at Radio Bilingüe while teaching there, Rios-Alvarado added.

Arroyo said he met Ríos-Bustamante while finishing his graduate studies at UCLA and introduced him to a group of scholars to chronicle a complete history of Mexicans in the United States. Often, Arroyo said he found Ríos-Bustamante on campus early in the morning having not slept the night before. Instead, he had been researching and writing about the Chicano history topics they discussed in their previous meeting, Arroyo added. “He would put in my hands anywhere from three to 20 pages of typescript where he had been ruminating about the questions and come up with possible answers,” he said. “He could not seem to shut off his mind. He was always thinking about how we could develop our interpretation of Chicano history.”

Their research attempted to combat the idea that Mexicans were inherently foreigners in the U.S...